Terrain Renderer Design

m (Kris's Project Log moved to Terrain Renderer Design) |

m (Reverted edits by Ebybymic (Talk); changed back to last version by Kris Nicholson) |

||

| (10 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | == | + | == Introduction == |

| − | + | The title for my honours project is "GPU Based Algorithms for Terrain Texturing". My goal is to find interesting and useful texturing algorithms using graphics hardware, specifically for 3D terrain. | |

| − | + | To help me with this my supervisor, Mukundan, gave me code for a Terrain Renderer using the ROAM algorithm (as far as I know this was written by a previous honours student). This meant I could focus on the texturing and GPU side of things, rather than the geometry. The majority of the current system was not written by me. In fact I have initially only added 2 classes. The code is written in C++ using OpenGL, GLUT and GLEW. | |

| − | + | === Shaders === | |

| − | + | Shaders are basically pieces of code that run on graphics hardware. There are three types of shaders; geometry, vertex and fragment/pixel shaders. I only use vertex and fragment shaders (geometry shaders are pretty new). Vertex shaders are called for every vertex that is drawn, so they are generally responsible for transforming vertices, generating texture coordinates and possibly lighting. Fragment shaders are called for every pixel (or multiple times per pixel, hence the term fragment) that is drawn. They are responsible for setting the colour at every point, so generally they will use textures and lighting and combine them in the way you want. | |

| − | + | By nature shaders are very hardware dependant. Not so much as assembly code, but some functionality is only available on some hardware. For example, it's only fairly recently (last 2 or 3 years) that shaders have supported dynamic branching (if then else) and even now, some hardware implements it in a way that you would not expect that can result in slow performance unexpectedly. | |

| − | + | To get a shader to do something reasonably interesting, you need a way to pass information to it. This can be done either with textures, or with uniform variables. A uniform variable is set from your main code using an OpenGL function (unless you're using DirectX of course, but that's not me). To do this, you need to know the name of the variable defined in the shader, so this means your main code is coupled to the shader. Which sort of makes sense if they need to cooperate to provide a particular effect. | |

| − | + | In terms of my design, I should try to abstract away from the shaders as much as possible, but there is always going to be some degree of coupling there. | |

| − | + | [[Image:terrainEx.jpg|center]] | |

| − | + | == Initial Design == | |

[[Image:texture1.png|thumb]] | [[Image:texture1.png|thumb]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Here is the initial design of the texturing side of the Terrain Renderer. The main piece of code contains one of each kind of Texture. The rendering can then be switched between each texture at runtime. Here's an overview of what each Texture does. | |

| + | * '''ProceduralTexture''' - A texture made up of multiple images. When created, the images are arranged and blended based on the terrain heightmap (higher regions have snow, lower regions have grass etc). This texture is applied 1-1 to the terrain. | ||

| + | * '''DetailMap''' - A DetailMap augments the ProceduralTexture method by using hardware Multitexturing to blend some small details to the terrain. The details are repeated a set amount across the terrain. | ||

| + | * '''TriGridTexture''' - Mainly for debugging, a TriGridTexture is created mathematically and applied to each polygon of the terrain individually. This way the polygon structure and number can be seen easily. | ||

| + | * '''BasicTexture''' - An almost empty class which implements the simplest kind of texture. One that is loaded from a file. However, this particular Texture doesn't know how to draw itself. It is only used by ShaderSplat. | ||

| + | * '''ShaderSplat''' - ShaderSplat performs texturing and lighting using Shaders. It doesn't actually contain any texture information, instead it passes some BasicTextures through to the Shaders to process. | ||

| + | In addition to this there is the shader code which consists of two files, a vertex shader and a fragment shader which are compiled and linked at load-time. | ||

| + | === Critique === | ||

| + | At this stage, Texture seems to have several responsibilities and is therefore a violation of the [[Single responsibility principle]]. It is responsible for the OpenGL representation of a texture in video memory as well as how textures are applied to the terrain surface. This may not seem all that terrible, but it limits the capabilities of some of the methods. For example, in the case of the DetailMap, it can only contain a ProceduralTexture but there is no particularly good reason for this to be. If we allow it to contain an abstract Texture, this would allow it to contain a ShaderSplat Texture. Since both these Textures use the graphics hardware directly, it is extremely unlikely that these would cooperate. | ||

| + | ShaderSplat also seems to be exhibit the [[Large class smell]]. In particular it currently keeps track of the location of each uniform variable in the shader code as seperate variables. It also contains multiple other textures (not seperate Texture classes) to do its job, such as a normal map (which is technically lighting data, but is stored in a texture format and can still be displayed like any other texture). It also has a fairly large interface (which could possibly be a [[Fat interfaces|Fat interface]]), since all the interactive pieces of the shader are passed through this object (such as whether certain features are enabled and parameters like the height levels to assign different textures to). | ||

| − | + | One maxim that the current design does follow is [[Tell, don't ask]]. There are a number of variables in ShaderSplat that are linked to shader uniform variables. These variables can be edited at run-time by pressing various keyboard keys. The obvious way to do this would be for ShaderSplat to have [[Getters and setters|getters and setters]] for each variable. But I decided to reflect its use more closely. That is, for boolean values, we will only ever want to toggle the value, and for numerical values we only ever want to increase or decrease the value (negative values can be used to decrease values). This way, the client will not be dependent on how ShaderSplat implements these values, allowing it to change easily. | |

| − | [[ | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | == Seperating Texture Responsibilities == | |

| + | [[Image:texture2.png|thumb]] | ||

| − | + | To seperate the two responsibilities of Texture, I created another hierarchy, called TexturingAlgorithm. As the name suggests, it was inspired by the [[Gang of Four|GoF]] [[Strategy]] design pattern as well as the [[State]] pattern. This is because although it represents a particular way of texturing, it also defines the OpenGL state for that method. The state is a combination of which Textures are bound and possibly the shader program that is to be run. useCoordsForPoint() is the main operation it is responsible for, where texture coordinates are generated for the particular vertex. Although not visible in the diagram, a number of TexturingAlgorithms are contained within the terrain rendering code. These algorithms can be switched at runtime (however, they need to be told this explicitly using the use() and clear() methods to setup and cleanup respectively, since it would be far too costly to do this for every vertex of every frame). In doing this I have essentially created classes defined by their behaviour, which is basically the same as using a verb for the class name (I suppose Texture would be the name if used as a verb, which would be confusing), which is generally not a good idea. However, since the [[Gang of Four|GoF]] [[Strategy]] pattern specifically does this also, there is some justification for doing so. | |

| − | One interesting thing to note is that we now have a distinct difference between a ProceduralTexture, which uses Images to create a Texture at load-time and a ShaderTexturingAlgorithm which uses Textures and combines them in a similar way in | + | One interesting thing to note is that we now have a distinct difference between a ProceduralTexture, which uses Images to create a Texture at load-time and a ShaderTexturingAlgorithm which uses Textures and combines them in a similar way at runtime. The main differences are that ShaderTexturingAlgorithm can change paramaters of this combination in realtime, but requires fairly modern graphics hardware to do so. |

| − | + | Here is a description of each class and what they are responsible for: | |

| − | + | * '''Texture''' - Represents an OpenGL texture. Holds a reference to it and knows how to bind and unbind itself to/from OpenGL. Also knows the length and width of the rendered terrain, which is necessary for some of the subclasses. | |

| + | * '''ImageFileTexture''' - Loads an image file into an OpenGL texture. | ||

| + | * '''ProceduralTexture''' - Loads multiple image files and combines them into one OpenGL texture based on the particular terrain. | ||

| + | * '''TriGridTexture''' - Creates an OpenGL texture with particular properties from geometric equations. | ||

| − | + | * '''TexturingAlgorithm''' - Controls the current texture (and shader) bindings and how texture coordinates are generated. | |

| + | * '''BasicTexturingAlgorithm''' - Applies a texture to the terrain directly. | ||

| + | * '''MultitexturingAlgorithm''' - Applies a texture to the terrain directly and uses hardware multitexturing with another texture which is repeated a number of times over the terrain. | ||

| + | * '''TriGridTexturingAlgorithm''' - Applies an entire texture once per polygon. | ||

| + | * '''ShaderTexturingAlgorithm''' - Interfaces with OpenGL Shader Language (GLSL) shaders to texture and light the terrain using a number of textures. | ||

| − | == | + | == Extracting Texture Classes == |

[[Image:texture3.png|thumb]] | [[Image:texture3.png|thumb]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | Because ShaderTexturingAlgorithm contained a couple of Textures that it used, I thought it was a good idea to separate these. These Textures were the NormalMap and the HeightMapTexture. The NormalMap contains the normal vector directions at every point on the terrain and is used for lighting calculations in the Shader code. The HeightMapTexture (which is named so to distinguish it from the HeightMap class elsewhere in the code, which does, believe it or not, describe a different idea) is a monochrome texture which stores the height of the terrain at each point. This will be more accurate than the geometry itself which is an approximation of the heightmap. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == Seperating Basic Shader Responsibilities From ShaderTexturingAlgorithm == | |

| − | + | Shaders obviously embody a separate idea to the algorithm that uses them, so following [[Model the real world]] it makes sense to extract any shader interface code into other classes. | |

| − | + | The structure and use of shaders are as follows: | |

| + | |||

| + | There are two main types of shaders, vertex and fragment shaders. These are pieces of code that can be loaded from files, but in my case they are always loaded from files. These are individually compiled, then attached to a shader program, where they are linked. To access uniform variables contained within the shader, the location of the variables must be known. The shader program can locate a variable given its name. It can also load a value into a variable given its location. The shader program can be set as the current shader program in execution. To return to the standard fixed function pipeline (no shaders), a null shader program needs to be used. | ||

| + | |||

| + | I decided to reflect this structure in classes as follows: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:texture6.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The ShaderProgram class wraps the GLSL shader program. It contains a map to store variable names and their locations. A shader wraps the GLSL shader. It is subclassed into the VertexShader and the FragmentShader. Shaders can be attached to a ShaderProgram after being compiled. The ShaderProgram can then be linked. After linking the program can be used and cleared. | ||

| + | |||

| + | I decided to reflect the underlying model in the interface to these clases. That is, a shader needs to be explicitly compiled by the client after creation. These are then attached, one by one, to the shader program. The program then needs to be explicitly linked by the client. I could have compiled the Shader automatically directly after loading from the file (which is done in the constructor). I could have also given the ShaderProgram a list of Shaders to link automatically. The reason I have done this is that there may be situations I am unaware of where direct control like this is necessary. Also in the case of the shader program, there is no less complexity in creating a list to be passed to the constructor than in adding each Shader manually. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Because this responsibility is passed to the client, several methods have preconditions that will need to be fulfilled, otherwise GLSL errors will be generated and results will be undefined. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Precondition for ShaderProgram::link():''' Each shader attached to the program has been compiled. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Precondition for ShaderProgram::use():''' The program has been linked. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Regardless of this reflection of the underlying interface, the code still looks a lot cleaner. The shader setup code goes from this: | ||

//initialise shaders | //initialise shaders | ||

| Line 102: | Line 129: | ||

cout << shaderProgram->getLinkerOutput(); | cout << shaderProgram->getLinkerOutput(); | ||

| − | One thing | + | One interesting thing to note is how similar VertexShaders and FragmentShaders are. The only difference between them is one constant that is passed to OpenGL. Because of this, the Shader class was not abstract so I made an abstract method specifically to force it to be abstract. This may indicate that the subclasses are not different enough to warrant being separate. I at least wanted to make sure that the ShaderTexturingAlgorithm was not aware of the particular constants. |

| − | + | == Abstracting From the OpenGL Shader Language (GLSL) == | |

| + | At this point I thought it would be interesting to venture into abstracting from implementation details of the shaders as much as possible. I imagine that this is a fairly common problem, especially in regards to game development, where the same game is developed for multiple platforms running different graphics libraries. However, my initial instinct was to not bother. [[You ain't gonna need it|YAGNI]]. Especially as, since I am probably not familiar enough with other shader languages to really understand the similarities and differences between them, it seems foolish to attempt to predict the future. I decided to do it anyway, for the purposes of experimentation, knowing that it might come to rewriting this section again. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In saying that, what I wanted to do was abstract the Shader classes enough so that if the shader language is to change, only one change needs to be made to ShaderTexturingAlgorithm. I discovered that an [[Abstract Factory]] pattern achieved this requirement since the concrete shader and shader program classes will be related by the shader programming language, and this relation needs to be enforced. Here is the structure of the ShaderFactory: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:texture7.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | * '''ShaderFactory''' - An abstract factory that produces fragment shaders, vertex shaders and shader programs. | ||

| + | * '''GLSLShaderFactory''' - A concrete factory that produces GLSL fragment shaders, vertex shaders and shader programs. Implemented as a [[Singleton]] since there will only ever need to be one. | ||

| + | * '''ShaderProgram''' - An abstract shader program containing the interface for attaching and detaching shaders, linking shaders and adding and setting uniform variables. | ||

| + | * '''GLSLShaderProgram''' - A concrete shader program implemented using GLSL functions. | ||

| + | * '''Shader''' - An abstract shader containing the interface for compiling a shader as well as a concrete load method. | ||

| + | * '''GLSLShader''' - A concrete shader implemented using GLSL functions. | ||

| + | * '''GLSLFragmentShader''' - A concrete fragment shader using GLSL. | ||

| + | * '''GLSLVertexShader''' - A concrete vertex shader using GLSL. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To add a new shader language, such as Cg, all we would need to is create a new concrete ShaderFactory, a concrete ShaderProgram, and at least one concrete implementation of Shader. If fragment and vertex shaders are implemented in the same way, the factory could just give the same type of object for both types. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By designing the factory in this way, we are assuming that other shader languages will have a similar structure in the way that they should be used. That is, that shaders will always be attached to a shader program and linked in this way. However, even if this is not the case, it probably wouldn't be different enough to make it unworkable. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One problem with this design is that for a concrete GLSLShaderProgram to attach a Shader, it needs to be a GLSLShader, not just an abstract Shader. Currently this is done using an explicit cast. In its current state, it is possible that another ShaderFactory could be used to create a concrete shader other than a GLSLShader and attach that to a GLSLShaderProgram, which would cause a runtime exception. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Removing the Explicit Downcast == | ||

| + | |||

| + | One way to remove the cast is to use [[Double Dispatch]]. Updating the design as follows: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:texture8.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now when attach(Shader) is called, the GLSLShaderProgram will call attachtoGLSLProgram(this) on the Shader. GLSLShader will then call program.attachGLSLShader(this). It seems that this has solved the casting problem. However, there is a catch. Now each Shader implementation has to implement attachTo methods for every type of concrete ShaderProgram and each ShaderProgram has to implement attach methods for each type of Shader. If we are trying to attach the wrong type of shader, rather than crashing, we have control over what happens. It could quietly ignore the request, or more usefully it could output some feedback to the developer who managed to break the factory and mix different types of shaders and shader programs together. Although this is useful, it seems equivalent to catching an exception. We have also now greatly increased the coupling between the various implementations of shaders and shader programs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Final Design == | ||

| + | [[Image:texture4.png|thumb]] | ||

[[Image:texture5.png]] | [[Image:texture5.png]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Code == | ||

| + | |||

| + | If you want to view or compile and run the code, download this file: [[Media:TerrainCode.zip|TerrainCode.zip]] (65KB) (Note: you will need to have installed and configured the OpenGL GLUT and GLEW libraries to compile. Visual Studio 2008 solution included.) | ||

| + | |||

| + | If you are only interested in running the application, download this file: [[Media:TerrainBin.zip|TerrainBin.zip]] (300KB) | ||

| + | |||

| + | In either case, to run the application you will also need the following two resources (separated due to file size limits): [[Media:Textures.zip|Textures.zip]] (1.54MB), [[Media:HeightMap.zip|HeightMap.zip]] (1.51MB) | ||

| + | |||

| + | The application should run on most Windows computers, but if you want to use the ShaderTexturingAlgorithm, you will need a fairly recent graphics card (Nvidia Geforce 8000 series or higher). See the enclosed User Guide for more information on how to use the application. | ||

Latest revision as of 03:08, 25 November 2010

Contents |

Introduction

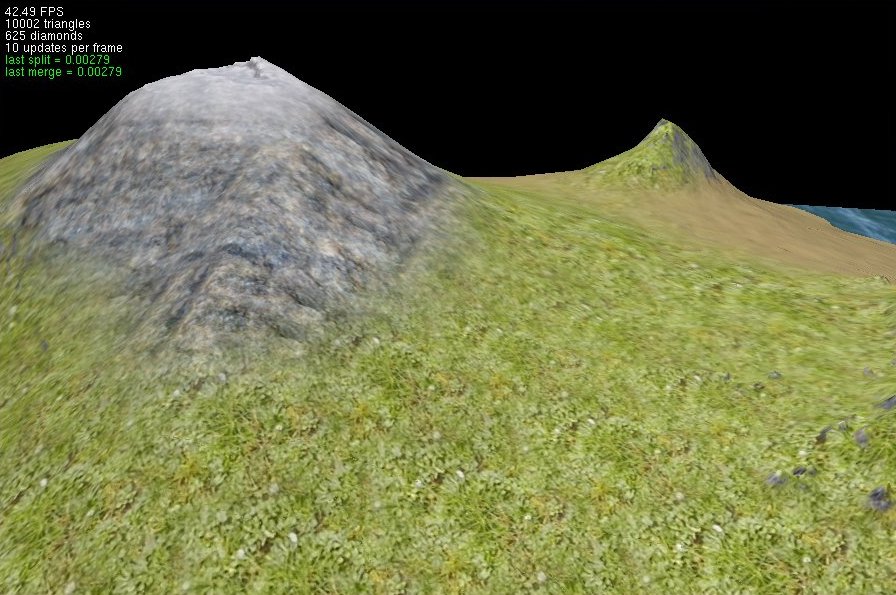

The title for my honours project is "GPU Based Algorithms for Terrain Texturing". My goal is to find interesting and useful texturing algorithms using graphics hardware, specifically for 3D terrain.

To help me with this my supervisor, Mukundan, gave me code for a Terrain Renderer using the ROAM algorithm (as far as I know this was written by a previous honours student). This meant I could focus on the texturing and GPU side of things, rather than the geometry. The majority of the current system was not written by me. In fact I have initially only added 2 classes. The code is written in C++ using OpenGL, GLUT and GLEW.

Shaders

Shaders are basically pieces of code that run on graphics hardware. There are three types of shaders; geometry, vertex and fragment/pixel shaders. I only use vertex and fragment shaders (geometry shaders are pretty new). Vertex shaders are called for every vertex that is drawn, so they are generally responsible for transforming vertices, generating texture coordinates and possibly lighting. Fragment shaders are called for every pixel (or multiple times per pixel, hence the term fragment) that is drawn. They are responsible for setting the colour at every point, so generally they will use textures and lighting and combine them in the way you want.

By nature shaders are very hardware dependant. Not so much as assembly code, but some functionality is only available on some hardware. For example, it's only fairly recently (last 2 or 3 years) that shaders have supported dynamic branching (if then else) and even now, some hardware implements it in a way that you would not expect that can result in slow performance unexpectedly.

To get a shader to do something reasonably interesting, you need a way to pass information to it. This can be done either with textures, or with uniform variables. A uniform variable is set from your main code using an OpenGL function (unless you're using DirectX of course, but that's not me). To do this, you need to know the name of the variable defined in the shader, so this means your main code is coupled to the shader. Which sort of makes sense if they need to cooperate to provide a particular effect.

In terms of my design, I should try to abstract away from the shaders as much as possible, but there is always going to be some degree of coupling there.

Initial Design

Here is the initial design of the texturing side of the Terrain Renderer. The main piece of code contains one of each kind of Texture. The rendering can then be switched between each texture at runtime. Here's an overview of what each Texture does.

- ProceduralTexture - A texture made up of multiple images. When created, the images are arranged and blended based on the terrain heightmap (higher regions have snow, lower regions have grass etc). This texture is applied 1-1 to the terrain.

- DetailMap - A DetailMap augments the ProceduralTexture method by using hardware Multitexturing to blend some small details to the terrain. The details are repeated a set amount across the terrain.

- TriGridTexture - Mainly for debugging, a TriGridTexture is created mathematically and applied to each polygon of the terrain individually. This way the polygon structure and number can be seen easily.

- BasicTexture - An almost empty class which implements the simplest kind of texture. One that is loaded from a file. However, this particular Texture doesn't know how to draw itself. It is only used by ShaderSplat.

- ShaderSplat - ShaderSplat performs texturing and lighting using Shaders. It doesn't actually contain any texture information, instead it passes some BasicTextures through to the Shaders to process.

In addition to this there is the shader code which consists of two files, a vertex shader and a fragment shader which are compiled and linked at load-time.

Critique

At this stage, Texture seems to have several responsibilities and is therefore a violation of the Single responsibility principle. It is responsible for the OpenGL representation of a texture in video memory as well as how textures are applied to the terrain surface. This may not seem all that terrible, but it limits the capabilities of some of the methods. For example, in the case of the DetailMap, it can only contain a ProceduralTexture but there is no particularly good reason for this to be. If we allow it to contain an abstract Texture, this would allow it to contain a ShaderSplat Texture. Since both these Textures use the graphics hardware directly, it is extremely unlikely that these would cooperate.

ShaderSplat also seems to be exhibit the Large class smell. In particular it currently keeps track of the location of each uniform variable in the shader code as seperate variables. It also contains multiple other textures (not seperate Texture classes) to do its job, such as a normal map (which is technically lighting data, but is stored in a texture format and can still be displayed like any other texture). It also has a fairly large interface (which could possibly be a Fat interface), since all the interactive pieces of the shader are passed through this object (such as whether certain features are enabled and parameters like the height levels to assign different textures to).

One maxim that the current design does follow is Tell, don't ask. There are a number of variables in ShaderSplat that are linked to shader uniform variables. These variables can be edited at run-time by pressing various keyboard keys. The obvious way to do this would be for ShaderSplat to have getters and setters for each variable. But I decided to reflect its use more closely. That is, for boolean values, we will only ever want to toggle the value, and for numerical values we only ever want to increase or decrease the value (negative values can be used to decrease values). This way, the client will not be dependent on how ShaderSplat implements these values, allowing it to change easily.

Seperating Texture Responsibilities

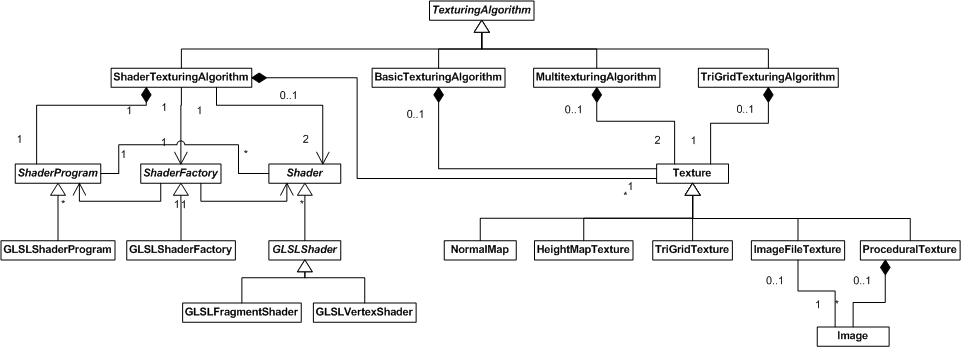

To seperate the two responsibilities of Texture, I created another hierarchy, called TexturingAlgorithm. As the name suggests, it was inspired by the GoF Strategy design pattern as well as the State pattern. This is because although it represents a particular way of texturing, it also defines the OpenGL state for that method. The state is a combination of which Textures are bound and possibly the shader program that is to be run. useCoordsForPoint() is the main operation it is responsible for, where texture coordinates are generated for the particular vertex. Although not visible in the diagram, a number of TexturingAlgorithms are contained within the terrain rendering code. These algorithms can be switched at runtime (however, they need to be told this explicitly using the use() and clear() methods to setup and cleanup respectively, since it would be far too costly to do this for every vertex of every frame). In doing this I have essentially created classes defined by their behaviour, which is basically the same as using a verb for the class name (I suppose Texture would be the name if used as a verb, which would be confusing), which is generally not a good idea. However, since the GoF Strategy pattern specifically does this also, there is some justification for doing so.

One interesting thing to note is that we now have a distinct difference between a ProceduralTexture, which uses Images to create a Texture at load-time and a ShaderTexturingAlgorithm which uses Textures and combines them in a similar way at runtime. The main differences are that ShaderTexturingAlgorithm can change paramaters of this combination in realtime, but requires fairly modern graphics hardware to do so.

Here is a description of each class and what they are responsible for:

- Texture - Represents an OpenGL texture. Holds a reference to it and knows how to bind and unbind itself to/from OpenGL. Also knows the length and width of the rendered terrain, which is necessary for some of the subclasses.

- ImageFileTexture - Loads an image file into an OpenGL texture.

- ProceduralTexture - Loads multiple image files and combines them into one OpenGL texture based on the particular terrain.

- TriGridTexture - Creates an OpenGL texture with particular properties from geometric equations.

- TexturingAlgorithm - Controls the current texture (and shader) bindings and how texture coordinates are generated.

- BasicTexturingAlgorithm - Applies a texture to the terrain directly.

- MultitexturingAlgorithm - Applies a texture to the terrain directly and uses hardware multitexturing with another texture which is repeated a number of times over the terrain.

- TriGridTexturingAlgorithm - Applies an entire texture once per polygon.

- ShaderTexturingAlgorithm - Interfaces with OpenGL Shader Language (GLSL) shaders to texture and light the terrain using a number of textures.

Extracting Texture Classes

Because ShaderTexturingAlgorithm contained a couple of Textures that it used, I thought it was a good idea to separate these. These Textures were the NormalMap and the HeightMapTexture. The NormalMap contains the normal vector directions at every point on the terrain and is used for lighting calculations in the Shader code. The HeightMapTexture (which is named so to distinguish it from the HeightMap class elsewhere in the code, which does, believe it or not, describe a different idea) is a monochrome texture which stores the height of the terrain at each point. This will be more accurate than the geometry itself which is an approximation of the heightmap.

Seperating Basic Shader Responsibilities From ShaderTexturingAlgorithm

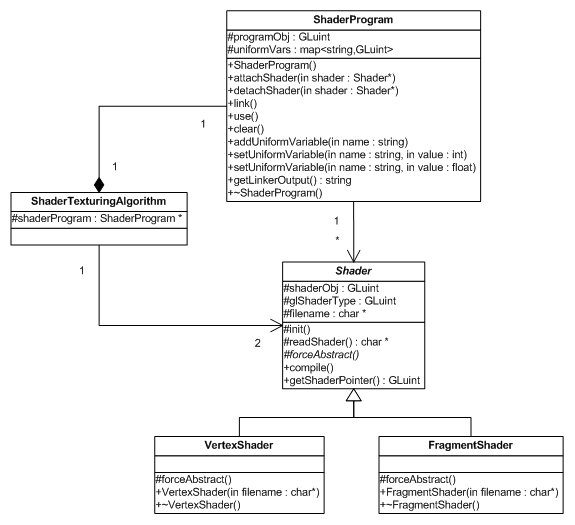

Shaders obviously embody a separate idea to the algorithm that uses them, so following Model the real world it makes sense to extract any shader interface code into other classes.

The structure and use of shaders are as follows:

There are two main types of shaders, vertex and fragment shaders. These are pieces of code that can be loaded from files, but in my case they are always loaded from files. These are individually compiled, then attached to a shader program, where they are linked. To access uniform variables contained within the shader, the location of the variables must be known. The shader program can locate a variable given its name. It can also load a value into a variable given its location. The shader program can be set as the current shader program in execution. To return to the standard fixed function pipeline (no shaders), a null shader program needs to be used.

I decided to reflect this structure in classes as follows:

The ShaderProgram class wraps the GLSL shader program. It contains a map to store variable names and their locations. A shader wraps the GLSL shader. It is subclassed into the VertexShader and the FragmentShader. Shaders can be attached to a ShaderProgram after being compiled. The ShaderProgram can then be linked. After linking the program can be used and cleared.

I decided to reflect the underlying model in the interface to these clases. That is, a shader needs to be explicitly compiled by the client after creation. These are then attached, one by one, to the shader program. The program then needs to be explicitly linked by the client. I could have compiled the Shader automatically directly after loading from the file (which is done in the constructor). I could have also given the ShaderProgram a list of Shaders to link automatically. The reason I have done this is that there may be situations I am unaware of where direct control like this is necessary. Also in the case of the shader program, there is no less complexity in creating a list to be passed to the constructor than in adding each Shader manually.

Because this responsibility is passed to the client, several methods have preconditions that will need to be fulfilled, otherwise GLSL errors will be generated and results will be undefined.

Precondition for ShaderProgram::link(): Each shader attached to the program has been compiled.

Precondition for ShaderProgram::use(): The program has been linked.

Regardless of this reflection of the underlying interface, the code still looks a lot cleaner. The shader setup code goes from this:

//initialise shaders

glewInit();

vobj = glCreateShader(GL_VERTEX_SHADER);

fobj = glCreateShader(GL_FRAGMENT_SHADER);

const char * vs = readShader("mult.vert"); //Get shader source

const char * fs = readShader("mult.frag");

glShaderSource(vobj, 1, &vs, NULL); //Construct shader objects

glShaderSource(fobj, 1, &fs, NULL);

glCompileShader(vobj); //Compile shaders

glCompileShader(fobj);

pobj = glCreateProgram();

glAttachShader(pobj, vobj);

glAttachShader(pobj, fobj);

glLinkProgram(pobj);

GLsizei *length = NULL;

GLcharARB *infoLog = new GLcharARB[5000];

glGetInfoLogARB(pobj, 5000, length, infoLog);

cout << infoLog;

To this:

//initialise shaders

Shader *vertexShader = new VertexShader("mult.vert");

Shader *fragmentShader = new FragmentShader("mult.frag");

vertexShader->compile();

fragmentShader->compile();

shaderProgram = new ShaderProgram();

shaderProgram->attachShader(vertexShader);

shaderProgram->attachShader(fragmentShader);

shaderProgram->link();

cout << shaderProgram->getLinkerOutput();

One interesting thing to note is how similar VertexShaders and FragmentShaders are. The only difference between them is one constant that is passed to OpenGL. Because of this, the Shader class was not abstract so I made an abstract method specifically to force it to be abstract. This may indicate that the subclasses are not different enough to warrant being separate. I at least wanted to make sure that the ShaderTexturingAlgorithm was not aware of the particular constants.

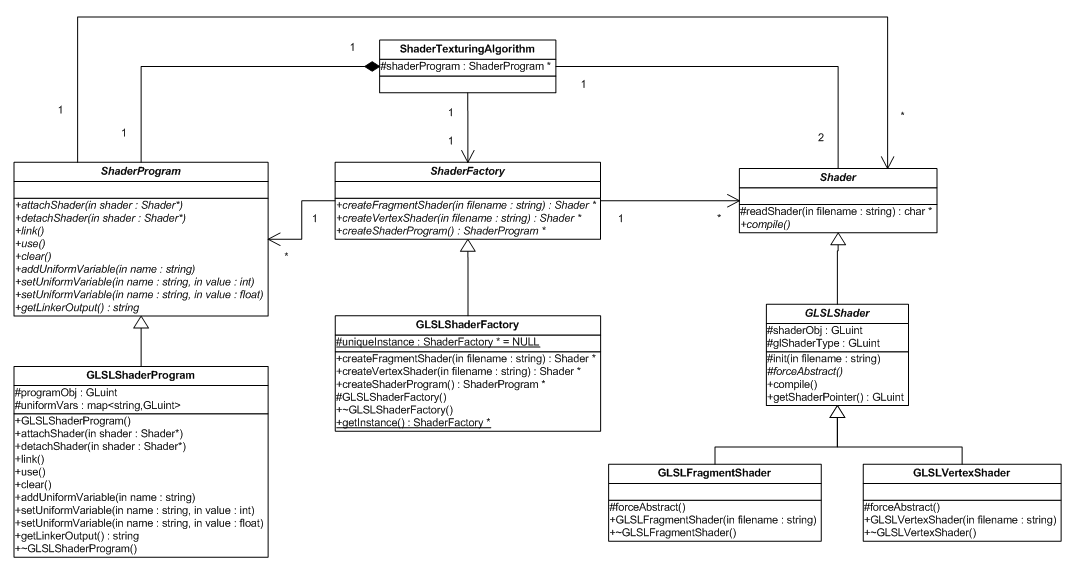

Abstracting From the OpenGL Shader Language (GLSL)

At this point I thought it would be interesting to venture into abstracting from implementation details of the shaders as much as possible. I imagine that this is a fairly common problem, especially in regards to game development, where the same game is developed for multiple platforms running different graphics libraries. However, my initial instinct was to not bother. YAGNI. Especially as, since I am probably not familiar enough with other shader languages to really understand the similarities and differences between them, it seems foolish to attempt to predict the future. I decided to do it anyway, for the purposes of experimentation, knowing that it might come to rewriting this section again.

In saying that, what I wanted to do was abstract the Shader classes enough so that if the shader language is to change, only one change needs to be made to ShaderTexturingAlgorithm. I discovered that an Abstract Factory pattern achieved this requirement since the concrete shader and shader program classes will be related by the shader programming language, and this relation needs to be enforced. Here is the structure of the ShaderFactory:

- ShaderFactory - An abstract factory that produces fragment shaders, vertex shaders and shader programs.

- GLSLShaderFactory - A concrete factory that produces GLSL fragment shaders, vertex shaders and shader programs. Implemented as a Singleton since there will only ever need to be one.

- ShaderProgram - An abstract shader program containing the interface for attaching and detaching shaders, linking shaders and adding and setting uniform variables.

- GLSLShaderProgram - A concrete shader program implemented using GLSL functions.

- Shader - An abstract shader containing the interface for compiling a shader as well as a concrete load method.

- GLSLShader - A concrete shader implemented using GLSL functions.

- GLSLFragmentShader - A concrete fragment shader using GLSL.

- GLSLVertexShader - A concrete vertex shader using GLSL.

To add a new shader language, such as Cg, all we would need to is create a new concrete ShaderFactory, a concrete ShaderProgram, and at least one concrete implementation of Shader. If fragment and vertex shaders are implemented in the same way, the factory could just give the same type of object for both types.

By designing the factory in this way, we are assuming that other shader languages will have a similar structure in the way that they should be used. That is, that shaders will always be attached to a shader program and linked in this way. However, even if this is not the case, it probably wouldn't be different enough to make it unworkable.

One problem with this design is that for a concrete GLSLShaderProgram to attach a Shader, it needs to be a GLSLShader, not just an abstract Shader. Currently this is done using an explicit cast. In its current state, it is possible that another ShaderFactory could be used to create a concrete shader other than a GLSLShader and attach that to a GLSLShaderProgram, which would cause a runtime exception.

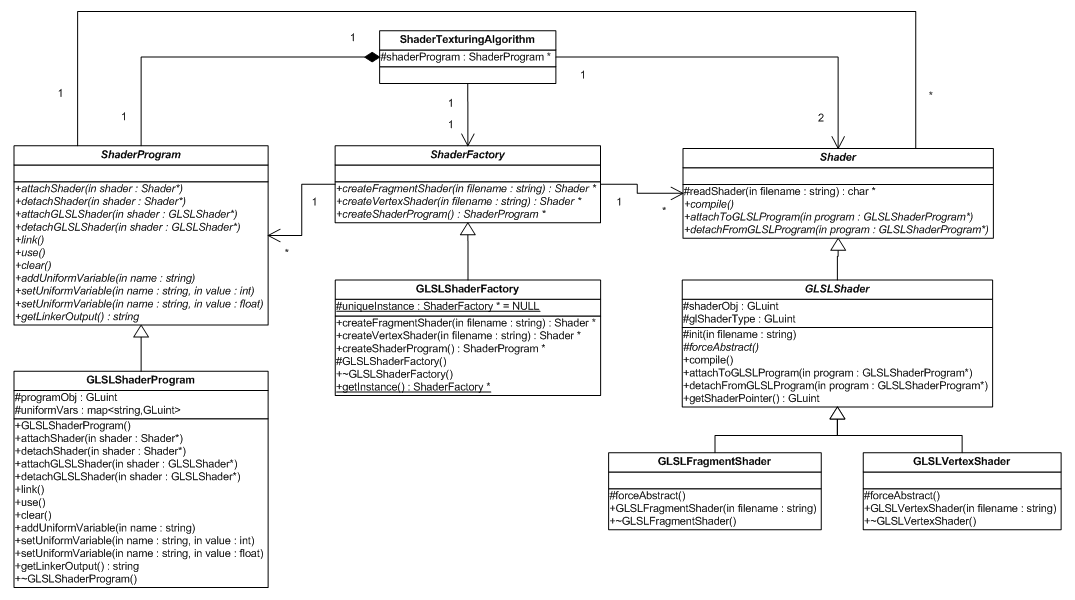

Removing the Explicit Downcast

One way to remove the cast is to use Double Dispatch. Updating the design as follows:

Now when attach(Shader) is called, the GLSLShaderProgram will call attachtoGLSLProgram(this) on the Shader. GLSLShader will then call program.attachGLSLShader(this). It seems that this has solved the casting problem. However, there is a catch. Now each Shader implementation has to implement attachTo methods for every type of concrete ShaderProgram and each ShaderProgram has to implement attach methods for each type of Shader. If we are trying to attach the wrong type of shader, rather than crashing, we have control over what happens. It could quietly ignore the request, or more usefully it could output some feedback to the developer who managed to break the factory and mix different types of shaders and shader programs together. Although this is useful, it seems equivalent to catching an exception. We have also now greatly increased the coupling between the various implementations of shaders and shader programs.

Final Design

Code

If you want to view or compile and run the code, download this file: TerrainCode.zip (65KB) (Note: you will need to have installed and configured the OpenGL GLUT and GLEW libraries to compile. Visual Studio 2008 solution included.)

If you are only interested in running the application, download this file: TerrainBin.zip (300KB)

In either case, to run the application you will also need the following two resources (separated due to file size limits): Textures.zip (1.54MB), HeightMap.zip (1.51MB)

The application should run on most Windows computers, but if you want to use the ShaderTexturingAlgorithm, you will need a fairly recent graphics card (Nvidia Geforce 8000 series or higher). See the enclosed User Guide for more information on how to use the application.