Command query separation

(→Examples) |

Jenny Harlow (Talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

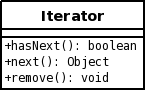

The Java Iterator class breaks CQS. The next() method is both a command and a query. It is a command because it moves the pointer to the next element; it is a query because it returns the element from the collection. The Java developers probably did this because they felt that every time you get an element, you will also want to update the pointer, so they thought it would save one call if next() did both functions. It can be argued that this is going too far in trying to make it simple, and results in an unclean design. | The Java Iterator class breaks CQS. The next() method is both a command and a query. It is a command because it moves the pointer to the next element; it is a query because it returns the element from the collection. The Java developers probably did this because they felt that every time you get an element, you will also want to update the pointer, so they thought it would save one call if next() did both functions. It can be argued that this is going too far in trying to make it simple, and results in an unclean design. | ||

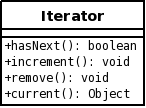

| − | A solution would be to break next() into two calls: current(), that returns the | + | A solution would be to break next() into two calls: current(), that returns the current element, and increment() which moves the pointer to the next element. |

Java implementation of Iterator: (breaks CQS) | Java implementation of Iterator: (breaks CQS) | ||

Revision as of 10:37, 19 August 2010

Command-Query separation (CQS) states that every method should either be a command that performs an action, or a query that returns data to the caller, but not both. Methods that return a value should be referentially transparent, and posses no side effects. wikipedia.org

A trivial example of this is getters and setters: Setters are commands that perform actions (setting a value), and getters are queries that return information about the state of the program. Getters do not change the state, and setters do not return a value.

CQS can be used quite well with a Design by contract approach to programming. In design by contract, assertions on the state of the program are considered as annotations, rather than programming logic. This means that querying the state (eg assertions) should not effect the program in anyway. When using CQS, any assertion can call a "Query" method, without having to worry about modifying the systems state.

CQS can simplify the development of a program, as programmers will always know that a method that returns a value has no side effects. Programmers are free to query the state of the system at any point without concern.

CQS suits the object-oriented approach to programming, but is not limited to it; it can be implemented in a procedural language with similar effects.

Examples

A simple example of a pattern that breaks CQS:

private int x;

public int value() {

x = x + 1;

return x;

}

Obeying CQS:

private int x;

public int value() {

return x;

}

public void increment_x() {

x = x + 1;

}

CQS broken in Java:

The Java Iterator class breaks CQS. The next() method is both a command and a query. It is a command because it moves the pointer to the next element; it is a query because it returns the element from the collection. The Java developers probably did this because they felt that every time you get an element, you will also want to update the pointer, so they thought it would save one call if next() did both functions. It can be argued that this is going too far in trying to make it simple, and results in an unclean design.

A solution would be to break next() into two calls: current(), that returns the current element, and increment() which moves the pointer to the next element.

Java implementation of Iterator: (breaks CQS)

Possible redesign: (obeys CQS)